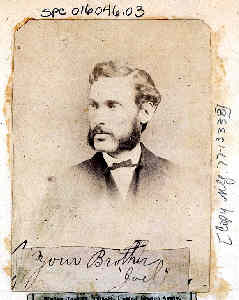

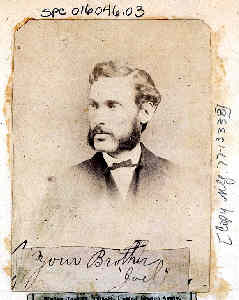

Source of Picture: Mark Davis

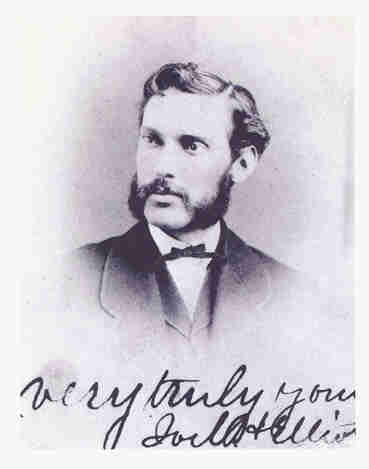

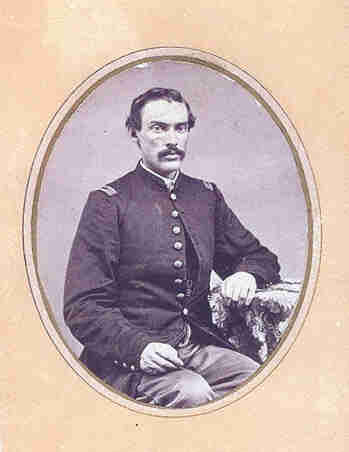

Source of Pictures: Lynn Endres

Photo I - Civilian Photo, circa 1866, between his stints in the army.

Photo II - In Uniform, is from the Civil War or just after the war, when he was with the 7th Indiana Cavalry. Probably taken in Memphis, TN.

Mark Davis, a descendant writes:

Joel Haworth Elliott, son of Mark Elliott and Mary S. Haworth was born October 27, 1840 in Wayne Co., Centre Township, Indiana, and died November 27, 1868 in White Rock, Indian Territory on the Washita River. Mary Haworth descends from George Haworth as follows:

George Haworth and Sarah Scarborough

James Haworth and Sarah Wood

Richard Haworth and Ann Dillon

Joel Haworth and Elizabeth Maxwell

Mary S Haworth and Mark Elliott

Joel H. Elliott

Joel Haworth Elliott was born to a stanch pacifist Quaker family in Wayne County, Indiana and lived on the family farm until the age of 21. Joel, however, ended up choosing a different path in life, which undoubtedly caused much concern to his family and Quaker friends. In the furor of the Civil War Joel H. Elliott was moved to enlist in Company C, 2nd Regiment, Indiana Volunteer Cavalry on August 28, 1861. He fought in various battles throughout the war and survived a critical wound to his left lung during the Battle of Brice's Cross Roads on June 10, 1864 in Guntown, Miss. He was commissioned Captain of Company M of the Seventh Indiana Cavalry on October 21, 1863. Through influence of Governor Morton, the Indiana war governor, he was raised to the rank of Major in the Seventh United States Cavalry.

The records of his Quaker Meeting make no mention of him during the time he fought for the Union during the Civil War. However, after the war when Joel decided to make his profession in the military, he was disowned from West Grove Friends Meeting, Wayne County, IN, 4th month,13th, 1867 "for serving in the army and accepting an office in the army." After the Civil War he served under the command of Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer in Kansas.

On 11 October 1867, at Fort Leavenworth, a court martial found Brevet Major General George Armstrong Custer, Lieutenant Colonel, 7th U.S. Cavalry guilty and sentenced him to suspension from rank and command for one year, and forfeiture of his pay for the same time. Major Joel Elliott was put in command of the 7th Cavalry during the year Custer was suspended from his command and his rank after being court marshaled.

[Source: http://leav-www.army.mil/history/custer.htm]

In October of 1867 Major Joel Elliott took 150 men from the 7th U.S. Cavalry, and a battery of the 4th to Medicine Lodge Creek to meet with the five major plains tribes to sign a peace treaty. Artillery provided the escort for the "Peace Commission" who were to go to Medicine Lodge Creek (Kansas) and meet the Indians. The troops left Ft. Larned on October 12th, 1867 with over 200 wagons, 30 of which were filled with gifts for the Indians. They arrived at Medicine Lodge Creek on the morning of the 14th. Over 5000 Indians from five different tribes were present at that meeting. By Monday, October 28th, 1867 all tribes present (the Kiowa, the Comanche, the Kiowa-Apache, the Cheyenne and Arapahos) signed the "Medicine Lodge Peace Treaty."

(Source: www.cyberlodg.com)

Joel Elliott was killed a year later when Custer's 7th U.S. Cavalry lead a surprise attack at dawn on a sleeping Cheyenne village located at White Rock along the banks of the Washita River, Indian Territory. The date was November 27th, 1868. The chief of that band of Southern Cheyenne was Motatavo (Black Kettle). He and his wife were killed in that attack. Hanging from the top of his teepee were two flags, an American flag and a white flag. Chief Black Kettle had assured the members of that village that the Americans would not attack them as long as the American flag flew above his teepee. He was dead wrong.

The following statements are from the website of the National Park Service Washita Battlefield National Historic Site.

[Source: http://www.nps.gov/waba/story.htm]

"Black Kettle and Arapaho Chief Big Mouth went to Fort Cobb [Indian Territory] in November 1868 to petition General William B. Hazen for peace and protection. A respected leader of the Southern Cheyenne, Black Kettle had signed the Little Arkansas Treaty in 1865 and the Medicine Lodge Treaty in 1867. Hazen told them that he could not allow them to bring their people to Fort Cobb for protection because only General Sheridan, his field commander, or Lt. Col. George Custer, had that authority. Disappointed, the chiefs headed back to their people at the winter encampments on the Washita River."

"Black Kettle, who had just returned from Fort Cobb a few days before, had resisted the entreaties of some of his people, including his wife, to move their camp downriver closer to larger encampments of Cheyennes, Kiowas, and Apaches wintered there. He refused to believe that Sheridan would order an attack without first offering an opportunity for peace."

"Before dawn, the troopers attacked the 51 lodges, killing a number of men, women, and children. Custer reported about 100 killed, though Indian accounts claimed 11 warriors plus 19 women and children lost their lives. More than 50 Cheyennes were captured, mainly women and children. Custer's losses were light: 2 officers and 19 enlisted men killed. Most of the soldier casualties belonged to Major Joel Elliott's detachment, whose eastward foray was overrun by Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Kiowa warriors coming to Black Kettle's aid. Chief Black Kettle and his wife were killed in the attack."

"Following Sheridan's plan to cripple resistance, Custer ordered the slaughter of the Indian pony and mule herd estimated at more than 800 animals. The lodges of Black Kettle's people, with all their winter supply of food and clothing, were torched. Realizing now that many more Indians were threatening from the east, Custer feigned an attack toward their downriver camps, then quickly retreated to Camp Supply with his hostages."

J. R. Mead, writing in the Wichita Eagle many years after the battle, called the Washita affair a massacre of innocent Indians. The writer declared that Black Kettle was not a hostile and never had been, that General Hazen had given the chief a letter guaranteeing him and his band protection, and that when William Griffenstein, a friendly trader and afterwards mayor of Wichita, accused Sheridan of striking a camp of friendly Indians he was ordered out of the Indian territory by Sheridan and threatened with hanging if he returned. Source: The Wichita Daily Eagle, March 2, 1893. (It is of interest to know that the writer of this article, J. R. Mead, was the Indian trader at Wichita who was accused by Governor Crawford in 1867 of having sold arms and ammunition to hostile Indians.)

A letter written by Joel Elliott less than 30 days before his death in Indian Territory to Theodore Russell Davis, a significant frontier journalist and artist of that era:

"Camp 7th U.S. Cav.

"Near Ft. Dodge Kansas

"October 31st, 1868

"My dear Davis,

"Yours of Sept. 21st. reached me a short time ago. I fear I can give you but little satisfaction in most of your queries but will answer as much because 'I feel out of humor' [underlined] and so am fit for nothing but writing as from any other cause.

"A grand winter campaign is being planned. Our column of the seven companies of the 5th cavalry, commanded by Bat. Maj. genl. Sears, and to go south from Fort Lyon. One of ten companies of the 7th cav. to go south from Fort Dodge and from Fort Larned. Genl. Custer is to command our column. He is already here. The regiment is in much better shape than I ever saw it before. Genl. Custer and Col. West seem to agree in letting the "Dead past bury its dead". Both the 5th and 10th have been having a little brush or two with the Indians. These with Forsyth's fight on the Republican, which by the way was about the best thing that has been done for some years in the way of Indian fighting, make all the 'real war' [underlined] we have had. I recently read a long article in the "Herald" (from some scribbler who was trying to make some reputation for Genl. Sully out of his expedition to the Canadian in Sept. I have the honor to command the cavalry on that expedition and if it was 'fighting' [underlined twice] then Indian Wars must be a huge joke. (Don't allow this to be public if you please for "Old Sully" is an amiable old fellow and I would not like to hurt his feelings.) I see some of the papers are pittying the "Poor Indian" as usual, while the Peace Commisioners are making heros and saints of them again. I only wish some of the most enthusiastic of their admirers both male and female could have been the recipients of the "Noble Reds" kindnesses instead of the unfortunate settlers on the Saline and Solomon. One of the women brought into Fort Harker was ravished by twenty three of the villians and then shot through the body. Strange to say she bids fair to recover from all this. Ed. Wyncop is out in a letter defending the Indians. If he were not so insignificant I would like to see him "Touched up" in good style. Comstock was one of the first victims to the savages. He and a scout named Grover had visited the camp of "Black Kettle" a Cheyenne Chief then supposed to be friendly and were leaving it when they were followed and shot. Grover feigned death and escaped with his life. Comstock was killed the first fire. From some cause the Indians did not scalp him. He is the only one of our scouts who have been killed to my knowledge. Under present circumstances I think my chances of getting coyote skins are at least no better than they are of being 'eaten by the coyotes' [underlined]. We are in the field and 'move light' [underlined], which latter means as uncomfortable as possible.

"When I began this letter I had an idea of conveying to you my 'grumblings' [underlined)] about "Army Life on the Border" but have already written a tolerably long letter and haven't begun my subject yet. So I'l (sic) wait for a more favorable oportunity (sic). Many thanks for those stamps. If you owed me any you have a better memory than I have but I was just as glad to receive them as though you had been my debtor for a thousand."

Very truly yours,

____________________________

In Custer's report on the "Battle of the Washita" to Gen. Sheridan he wrote in part:

"The Indians left on the ground and in our possession, the bodies of 108 of their warriers, including "Black Kettle" himself, whose scalp is now in the possession of one of our Osage guides. My men charged the village, and reached the lodge before the Indians were aware of our presence. ..... We captured in good condition 875 horses, ponies and mules, 241 saddles, some of very fine and costly workmanship; 523 buffalo robes, 210 axes, 140 hatchets, 35 revolvers, 47 rifles, 535 pounds of powder, 1050 pounds of lead, 4,000 arrows, 90 bullet-molds, 35 bows and quivers, 12 shields, 300 pounds of bullets, 775 lariats, 940 buckskin saddle-bags, 470 blankets, 93 coats, 700 pounds of tobacco. In addition, we captured all their winter supply of dried buffalo meat, all their meal, flour, and other provisions, and, in fact, everything they possessed, even driving the warriors from the village with little or no clothing. We destroyed everything of value to the Indians."

[Source: http://www.hillsdale.edu/dept/History/War/America/Indian/1868-Washita-Custer.htm]

Mark Davis writes: It is my opinion that what is 'officially' referred to as the "Battle of the Washita" would be more truthfully and appropriately named the "Washita Massacre". This incursion was the second time that Chief Black Kettle's village had been attacked by soldiers of the U.S. army. The first massacre of this band's village took place in what is now Kiowa County, Colorado in 1864 and is "officially" dubbed the 'Sand Creek Massacre'.

For more info on the Sand Creek Massacre, see: http://www.nps.gov/sand/]

Joel Elliott's body along with the other 17 fallen soldiers was recovered from the battlefield two weeks later on December 11th, 1868. Major Elliott's body was taken to Ft. Arbuckle, Indian Territory for burial. After Ft. Arbuckle was decommissioned in 1870, his body was taken from there and laid to rest in the Officers' Circle at Ft. Gibson National Cemetery, Ft. Gibson, Muskogee Co., Oklahoma in 1872.

Source: http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=1216.

Editor's Note:

See on this web page "Silver Creek-Salem" for a picture of Joel Elliott's mother and siblings.

Obituary printed in the "Richmond (Indiana) Palladium", December 8, 1868:

"Major Joel H. Elliott, whose parents reside near Economy, in this county, was killed in the recent severe fight between the Indians and Custer's Command--Major Elliott entered the service as Lieutenant in the Seventh Indiana Cavalry, and by meritorious conduct was promoted, step by step, until he attained the rank of Major, in the regular Army." --Telegram

In 1875 Fort Elliott, a military post, was established in Wheeler County, Texas. Troops from Fort Elliott patrolled both the Panhandle and western Indian Territory. Their main task was to stop small hunting parties of Indians from entering the Panhandle, but on several occasions during the late 1870s they pursued bands seeking to escape the reservation. Fort Elliott was named in honor of Major Joel H. Elliott, who lost his life while participating in the U.S. government's genocide of the Plains Indians.

The following letter accompanied the Indiana Distinguished Service Medal presented to Major Joel H. Elliott (posthumously) for Outstanding Meritorious Service.

MILITARY DEPARTMENT OF INDIANA

2002 South Holt Road

Indianapolis, Indiana 46241-4839

PERMANENT ORDERS 085-003 29 September 1997

"By direction of the Governor of the State of Indiana, under provisions IC 1971, 10-2-9-1 (b), the Indiana Distinguished Service Medal for unusual, distinguished, or meritorious service is awarded to:

MAJOR JOEL H. ELLIOTT

COMPANY M, 7TH INDIANA CAVALRY REGIMENT

(POSTHUMOUSLY)

"The Indiana Distinguished Service Medal (822) is hereby awarded to Major Joel H. Elliott for distinguishing himself by his heroism and leadership, while as a Captain, Commanding Company M, 7th Indiana Cavalry Regiment. Major Elliott participated in the expedition to Meridien, Mississippi, a retrograde movement to West Point, Mississippi, The Battle at Brice's Crossroads, and Grierson's Raid. The memory of Major Elliott's exemplary leadership, bravery, and loyalty to the colors he was serving, remain with us today as an inspiration and example to which all military personnel may aspire."

"BY THE ORDER OF ROBERT J. MITCHELL, Major General INARNG, the Adjutant General"

The face of the medal reads: "INDIANA - LOYAL IN PEACE OR WAR"

This medal is in the possession of the Wayne County Historical Museum, Richmond, Indiana.

Editor's Note: The above shown information was provided by Mark Davis, who descends from Joel Elliott's brother, William Elliott. Mr. Davis's linage is as follows:

George Haworth and Sarah Scarborough

James Haworth and Sarah Wood

Richard Haworth and Ann Dillon

Joel Haworth and Elizabeth Maxwell

Mary S Haworth and Mark Elliott

William Quincy Elliott and Rebecca Jane Jackson

Mark Haworth Elliott, Sr. and Mary Frances Guyer

Mark Haworth Elliott, Jr. and Mary Elsie Sophronia Harvey

Evelyn Lorene Elliott and John Alexander Davis

William Mark Davis

Mark Davis's web page can be found at:

Mark also writes: Sandy Barnard, an author and civil war historian, has written a biography on Major Joel H. Elliott. It is called "Custer and Elliott: Comrades in Controversy". Information on the book can be found at http://www.astpress.net/schedule.html

Here is Lynn Enders' research, starting with the reference in "Some Quaker Families- Scarborough/Haworth", Volume 1, Page 409

#610. MARY S. HAWORTH (daughter of Joel Haworth & Elizabeth Maxwell) m. MARK ELLIOTT (son of Exum Elliott & Catharine Lamb).

1364. iii. JOEL H. ELLIOTT

"d. Nov 1868, killed by Indians in the battle of Brice's Cross Roads, on the Washata River, now in OK; buried Ft. Arbuckle, OK, and later removed to Ft. Gibson National Cemetery, Miami, Ottawa, OK. "

In researching the story-behind-the-story, I started with the "Battle of Brice's Crossroads." There was indeed a battle at Brice's Crossroads, but it was called the Battle of Mississippi during the Civil War, June 10, 1864. Joel did, however, participate in this battle and was seriously injured at the time.

The next step was to look for the river itself. In Oklahoma there are two places by a similar name - Quachita (pronounced as you would Washata), and Washita. Both searches came up cold, until I sent out a plea to my family via our newsletter. A cousin who has long been interested in Western history recognized the name and combed through his own library to come up with the Battle of the Washita. I took a trip to far Western Oklahoma to the site of the Battle of the Washita along the Washita River and struck gold.

I started at the Black Kettle Museum in the town of Cheyenne, Oklahoma, and it was there that I found our Major Joel H. Elliott. I left there, fully armed with the story, and spent the rest of the afternoon at the actual battle site. I was there in the heat of August, but could only imagine the troops and the Indians at the same place in the frigid temps of November. It is a barren and forbidding landscape.

IN BRIEF

Major Joel Elliott commanded 150 troops of the 7th Cavalry as escorts to the peace commission headed by Sen. John B. Henderson at Medicine Lodge. The Indians stood in the way of migration to the western states, overland transportation of mail and trade, building of the railroad, marketing of Texas beef in Kansas, homesteaders, and the expansion of new settlements. A peaceful solution was sought...either that or "severely punish the tribes by forcing them to remain on isolated reserves or outright kill them all."

Although all signed on the dotted line, it was considered by most a "mock treaty." Even in Elliott's official report of the council, he charged that not one word of the treaty was actually read to the chiefs. They had no idea what they were signing.

In May of 1868, the first sign of trouble with the Indians surfaced and it was decided to launch a major campaign against the Indians of Oklahoma and Kansas, of which Elliott and his men participated in. All were failures, so a new plan of attack was formulated - a winter attack.

Custer, who had been suspended from command, rank and pay for one year as a result of charges brought against him for desertion (among a long list of others), was brought back into commission to lead this attack. On November 12, 1868, led by Osage guides, Custer commanded 450 wagons, a herd of beef cattle, 11 companies of the 7th Cavalry, (led by Major Joel Elliott), 3 companies of the 3rd Infantry, 1 company of the 5th Infantry, and 1 of the 58th Infantry on their march into Indian Territory (now Oklahoma).

Early on the morning of November 27th, Elliott and his party struck the Cheyenne village of Black Kettle, (the most peaceful of the Cheyenne leaders), from the rear, unaware of the hundreds of other Indian villages that lay downstream from them. Approaching Kiowas and Arapahos, coming to the aid of the Cheyenne, took Elliott and his men by surprise. Elliott and his men were killed.

Elliott takes on importance at this point because Custer has refused to confirm Elliott's location or even his death, leaving them all behind. It isnít until Custer returns to Ft. Cobb, with his commanding officer, Sheridan, that Sheridan insists they make a final stop at the massacre site, and follow Elliott's last footsteps.

"A scene was now witnessed sufficiently to appall the bravest heart. Within an area of not more than 15 yards, lay the human bodies - all that remained of Elliott and his party. The winter air swept across the plain, and its cold blasts had added to the ghastliness of death the additional spectacle of naked corpses frozen as solidly as stone. There was not a single body that did not exhibit evidence of fearful mutilation. Bullet and arrow wounds covered the back of each; the throats of a number were cut, and several were beheaded." (Journalist DeB. Randolph Keim, who accompanied Custer into the massacre.)

The men were buried in a large trench on a small knoll overlooking the Washita valley, just west of the campsite. The grave was covered by logs and brush to keep wolves from digging it up. Elliott's body, however, was taken to Ft. Cobb, and then on to Ft. Arbuckle for interment.

Elliott had a large devoted following and most of the men disliked Custer with a passion. They wrote a letter about Custer, the massacre, and the fact that he had left Elliott and his men's bodies behind, that appeared in the New York Times and St. Louis Democrat. Many of these same men had to fight alongside Custer again at the Battle of Little Bighorn. I suspect that had Elliott survived the massacre at Washita, he, too, would have fought at the Battle of Little Bighorn. The Cheyennes refer to this battle as the "day of redemption" for Custer's actions in Indian Territory.

A little more about Joel.

Native of Indiana, served with the 7th Indiana Volunteer Cavalry during the Civil War. In June of 1864, at the Battle of Mississippi, he was shot in the lungs and shoulder and had his horse killed out from under him. He was so seriously wounded that he was left for dead on the battlefield. But by January of 1865, he was back in action with the 7th (not sure how he got to safety), and shortly commended for his untiring zeal and bravery in capturing a Rebel train during Grierson's famous raid.

He was mustered out of service in February 1866 and turned to teaching school for a time, becoming superintendent of the Toledo, OH, public schools. When the Union Army was reorganized for frontier duty, he joined up once again.

Joel H. Elliott d. November 27, 1868, at the Battle of the Washita. Buried Ft. Gibson National Cemetery, Ft. Gibson, Muskogee Co., Oklahoma.

Joel H. Elliott, Unmarried

Son of Mary S. Haworth & Mark Elliott

Mary dau of Joel Haworth & Elizabeth Maxwell

Joel son of Richard Haworth & Ann Dillon

Richard son of James Haworth & Sarah

Richard son of George Haworth & Sarah Scarborough

Photo I - Civilian Photo, circa 1866, between his stints in the army.

Photo II - In Uniform, is from the Civil War or just after the war, when he was with the 7th Indiana Cavalry. Probably taken in Memphis, TN.

There are hundreds of references to Major Joel Elliott - books, articles, internet - but for a good general read about the Battle of Washita, try "The Battle of the Washita" by Stan Hoig, 1976, University of Nebraska Press. At the back of this book is a precise and very detailed listing of those of Custer's troops (22) who were killed and how. I won't detail Elliott's death here, but you can read it for yourself, if you want.

This particular battle is a real sore point with historians, especially in Oklahoma. Most refer to it as "The Massacre at Washita."

Ron Haworth, editor